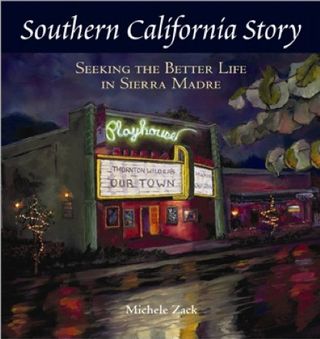

by Michele Zack

Special to Altadenablog

Our friend & Altadena historian Michele Zack's new book is Southern California Story: Seeking the Better Life in Sierra Madre. She shares with us her Dec. 2 talk at Vroman's Bookstore about the different "tribes" that inhabit the Tricities Area (Pasadena, Altadena, and Sierra Madre), and the surprising history of how illness shaped the character of these towns, and indeed all of Southern California.

Tribes of Settlers: the San Gabriel Valley, and the Illness Legacy

My new book clearly focuses on Sierra Madre, but at the same time is outward looking, I use this little San Gabriel Valley town as a lens through which to connect to neighbors, as well as to larger histories.

An anthropological bent runs deep in me. My father in law is an anthropologist, my husband skipped the 2nd grade to live with him and his mother in a mud hut on Mount Elgin in Uganda, and I myself wrote a popular ethnography of a wandering hill tribe in Southeast Asia. Some fellow Altadenans might remember being likened to the Lisu, who are sometimes called “the Anarchists of the Highlands,” when the Altadena book came out. I also invoked a Lisu aphorism I felt resonated with my home town: “It is better to live close to the water and far from the ruler.”

In studying the San Gabriel Valley, so far I’ve focused on three places, Altadena, Pasadena, and now Sierra Madre — and the micro-histories and cultures of each has always struck me as curiously distinct, as if different tribes of people settled them, even though they obviously have a lot in common. Cultural history, which has to do with the meaning people make of the times they are living through, often through art and books and other media, is something I love to explore. Here are a few distinctions that make these three places unique:

Pasadena was settled primarily by Protestant Midwesterners — strong Temperance people, in 1873. Of course my personal hero Benjamin Eaton had a lot to do with earliest development, and he was a Yankee and made great wine. But the series of migrations that populated the town during the first and second generations were dominated by friends and family from Indiana and Iowa, some from Ohio, a large share of whom had served in the Union Army and were ardent abolitionists. Sons of John Brown Owen and Jason, as well as his daughter Ruth Thompson (married to Henry Thompson, one of the few, like Owen Brown, who survived Harpers Ferry Raid and escaped the noose) are examples.

Pasadena’s early founders were intent on proving it was possible to establish an island of culture and civility in Southern California — which was still considered foreign, Mexican, Catholic, and Southern-minded. This was especially true of Los Angeles, which was rife with frowned upon activities such as crime, prostitution, lynchings, and mixing of races among the lower classes.The first Pasadenans founded the un-Los Angeles, immediately began building schools and churches and keeping alcohol sales out of town through the power of community agreement. Theirs was something of a Utopian vision, as land was purchased in common. Calvin Fletcher drew up an early plan that reflected enlightened city planning views influenced by Olmsted and Vaux, whose Central Park had been completed the year before the San Gabriel Valley Orange Grove Associated (precursor or Pasadena) incorporated as a land and water association. He drew curvilinear streets, set aside land for parks, and was inspired by highest civic ideals. These fairly quickly devolved into more practical sorts of development, but Pasadena’s wealth and high-mindedness immediately established the town as the gold standard in Southern California.

By contrast, Sierra Madre was subdivided and sold as a pure business deal a few years later, in 1881. However, founder N.C. Carter populated it very intentionally with an interesting mix of Old and New Englanders whom he’d handpicked on his Carter Excursions subsidized by the Big Four, and marketed as far away as Europe.

Carter was from Lowell, Massachusetts, America’s first planned industrialized town that grew up with the industrial revolution: spinning, weaving, textiles — and the legacy of the idealized Christian City Upon a Hill envisioned by first governor John Winthrop in 1630.

As Carter grew up, he saw pollution, racial and religious disharmony, and labor strife. Sierra Madre historian Elaine Wogenson has speculated Carter founded Sierra Madre as the Un-Lowell: no industry, but a heady dose of intellectual and artistic talent, religious people, many of whom were affected by the Transcendentalist Movement of the first half of the 19th century.

By the 1890s, perhaps half the people were British, with quite a few Canadians. Because it is a small place, it was notable that along with Brits, so many other Europeans were among the earliest settlers, Cigar-maker Emile Deutsch, was Belgium, Justus Kraft who was elected to the first Board of Trustees after the incorporation vote in 1907,was from Germany. John Pegler from Britain was also elected, and the first Mayor, C.W. Jones, had only been in town two years. Sierra Madre waited 26 years from founding to incorporation, and a new crew of settlers had arrived, many with a temperance agenda, who took over political control. These folks were quite different from founding settlers.

Altadena: different again. I’ve likened its civic construction to a pot of boiling stock to which some carrots, an onion, a chicken, and whatever other vegetables lying around are tossed into over the course of attending to other chores. The moment it “became soup” is arguable, although settlers were here even before Pasadena collectively bought land to the south. In fact Altadena never acquired the civic glue of incorporation that allows for local lawmaking. It has preferred to remain “far from the ruler” — the Los Angeles Board of Supervisors.

It developed as a mix of millionaires from Chicago, and farmers, (some millionaire farmers) particularly grape growers, who resisted every move of Pasadena’s to include it in their temperance regime. Benjamin Eaton, William Crank, the Allens, Colonel GG Green, Andrew McNally are some examples.

The Woodburys are an exception, as John Woodbury actually sat on Pasadena’s incorporation committee in 1886 as he was planning to market his new subdivision in Southern California’s great Real Estate boom of the mid-to-late 1880s. He didn’t mind sacrificing the family vineyards in order to join the ranks of real estate millionaires. His timing was seriously off, however, the boom busted about a month after he opened the subdivision. He’d invested way more money than he had in transportation infrastructure and advertising, and ended up leaving in disgrace and causing the family bank back in Marshalltown, Iowa to go under.

These are just very quick sketches of three towns. Of course there are overlaps and the towns have lots in common as well, yet each has a distinct personality.

While I use the word tribe somewhat tongue in cheek — there was a far larger tribe that many people in all three towns belonged to: the HEALTH SEEKERS, who comprised perhaps 25 percent of all westering settlers between the end of the Civil War and 1900. Sierra Madre, the smallest, most isolated of the three, had the largest concentration of sick people. No one was there who wasn’t sick himself or herself — or who had sickness in the family. That’s why people went there. To a lesser degree, this was true of Altadena and Pasadena.

It’s sort of anti-intuitive, but nonetheless true, that a big share of our hardy pioneers were sick and could not work. The only cure for tuberculosis was to move to a dry, warm climate, breathe clean air, and eat pure food before one’s case became too advanced. We didn’t have penicillin until around World War II, and isolating sick patients (which brought down infections rates) did not begin in earnest until around 1900. Sick settlers who came to Southern California did not come in covered wagons; they mostly arrived on the new Transcontinental Railway, finished in 1869. People already in California looking to sell land did not think a big consumptive camp would make for good ad copy, and tended to stifle facts about how many sick people were here. A.C. Vroman, ancestor of our hosts tonight, witnessed a camp of dying indigents in the foothills behind Altadena and wrote of the misery of those coming West only to die in the sunshine.

This was a huge worry in Sierra Madre, but in fact most sick people were quite well-heeled, and taken care of by women at home or in small private facilities. Many, such as N.C. Carter, recovered completely. He is one of the few who advertised his illness — and recovery — in print media all over the Northeastern United States and in Europe.

More typically, sickness was a private matter kept within the family, and the obituary column was the only proper place to mention death. But when you look at all the unbackbreaking, intellectual, and artistic pursuits of Sierra Madreans, and many from Pasadena and Altadena — painting, writing, decorating church organs, watching oranges grow, and putting on endless plays and entertainments for each other, you realize that this tribe seeded the entire Southland with an unusual degree of creativity, and that its legacy lives on in the creative culture of our region today: movies, art, writing, etc, — Southern California is indeed a leader in all of these.

I believe while illness as a motivator for immigration has been well described by historians, its legacy is something we need to take a closer look at — I believe it is huge, and goes a long way toward understanding California’s cultural history.

We’re still obsessed with health, nature, and food, much as early settlers must have been obsessed with the fantasy of recovering their health in this sunny arcadia and the possibility of a better life. TB infections rates went down, and a cure was finally found, but California’s intense allure has always been associated with fantasy: a past of happy Indians at the Missions, agricultural fantasies, and the fantasies of the silver screen. Imagination spilled over into marketing, real estate, and the film industry, and are important aspects of the Southern California story I was able to look at under the microscope, so to speak, in little Sierra Madre.