The artists gather here about every two weeks, some from far away -- sometimes Orange County, sometimes Santa Barbara, and today one from San Luis Obispo. They bend over their work, using pigments suspended in an emulsion of egg white and white wine, using delicate brushes and gold leaf. Their purpose? Making windows into Heaven.

The Icon Guild of Southern California is a group of artists creating icons in the Russian-Byzantine style. They are not icon “painters”; in the parlance of Eastern Orthodoxy, the stream of Christianity where icons developed and are most revered, the creators are “icon writers.”

“It is a spiritual exercise for all of us,” said Edward Beckett. “Your are making objects that are used in worship, as a focus for prayer in homes and churches.”

Beckett is an Altadena painter, sculptor, and printmaker who hosts the Guild’s gatherings in his bright, sunlit home studio on Altadena Dr. He was attracted to icon writing, almost despite himself.

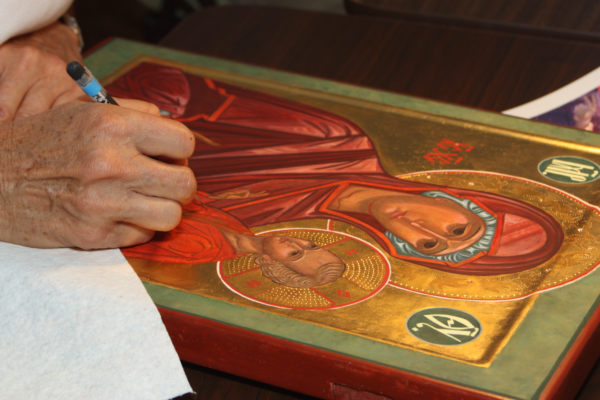

Pictured: Edward Beckett demonstrates

a brush technique

to budding icon writer

Marguarite Lyons.

Beckett’s wife and greatest booster Sharon Bailey Beckett saw an advertisement in the Episcopal News several years go for an icon class, and thought Edward would be interested in it. He wasn’t at first, he said, “but she kept after me. I went to partake in the class, and it was really terrific.”

Pictured: Theresa Rohter works

from a picture of another icon

to study the drape of clothing.

And so the Guild was born. The Guild has been in existence for seven years, its members attracted to the art, craft, and discipline of making these ancient holy images. The members come from all branches of liturgical Christianity: the icon writers this particular Saturday are Marguarite Lyons of San Luis Obispo, a Roman Catholic; Theresa Rohter of Santa Barbara, also Roman Catholic; and Dorothy Alexander of Santa Barbara, a member of the Antiochian Orthodox Church. Some members travel from as far south as Orange County. Beckett identifies himself as an Episcopalian.

Beckett is in training to be an instructor with the Prosopon school of Russian-Byzantine iconography founded by Vladislav Andrejev, who now lives in New York state. Sharon says that Edward was attracted to the Prosopon by the strictness and theology behind it. In order to be an approved Prosopon instructor, Edward Beckett said, he must learn more of the theological thought that lies behind every image in every painting.

Pictured: Dorothy Alexander works

on painting the frame of her icon.

“I’ve pretty much got the technical side, after so many years of being an artist,” Beckett said. Now, the journey involves learning the theological and symbolic meanings behind the image.

“It’s not just a picture,” Beckett says. “It’s a story, and a narrative.”

Pictured: detail of Dorothy Alexander's icon.

Pictured: detail of Dorothy Alexander's icon.

Alexander puts her icon on a kitchen Lazy Susan

so she can easily paint from any angle.

The theological message even extends to getting just right the fabric that each person in the icon is wearing -- wool, from animals, representing the base, human self; linen, from plants, which represents a higher spiritual reality; and all divine creatures, such as angels, are garbed in shimmering silk. Learning how to convey the textures of the cloth on the wooden painting surface is an important part of the icon writer’s art.

Pictured: a selection of pigments

used to write an icon.

Today, the group members are each writing the same image of the Theotokos -- the God-bearer, the Virgin Mary. Each icon writer is working from a pattern, a model image, attempting to learn and reproduce each color, each gesture, each fold of cloth.

Pictured: a candle burns in the altar corner of Beckett's studio.

There are no tubes of paint on the icon writers’ work area. From antiquity, icons have been made in only natural materials: birch wood boards primed in gesso, a concoction of calcium carbonate and animal glue; gold leaf; and the egg-and-wine tempera using ground pigments.

The result today is a vibrantly-colored image of the Theotokos and child Christ. Icons were first described around 300 AD. The earliest known surviving icon is a Christ Pantocrator (Christ the Creator) circa 500 AD, and its colors are still bright, a millennium and a half later.

The Theotokos they’re working on today has a gold leaf halo that breaks the frame. The work is slow, deliberate, suffused with prayer. Dorothy Alexander says that, with each application of bit of gold leaf, one must breathe out three times -- for Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.

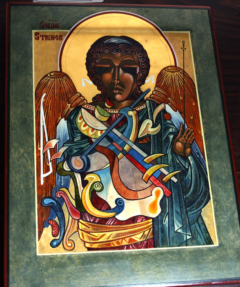

Sharon Bailey Beckett displays

Edward's secular icon of the

guardian angel of Sopranos.

Beckett says that each icon goes through 21 steps in its creation. The final step is having the image blessed by a priest. The Guild members are working with the University of Southern California to have their icons blessed in an ecumenical service on campus after they are finished.

But it’s not only the sacred icons that attract Beckett. According to Sharon, who is not only a supporter but interpreter of her husband’s work, Edward was so moved by the icons as a focus for meditation, that he is creating a series of “secular icons” -- using iconographic skills and tropes for people in various jobs and professions, to use as a focus for meditation. “It’s his belief that all professions need a place to meditate,” Sharon says.

Pictured: the secular icon

of the guardian angel of Strings.

He is in the midst of a series of secular icons for musicians -- guardian angels for sopranos, tenors, and altos; a keyboard angel; an angel of strings; a conductor. Beckett is a ekphrastic artist, Sharon says -- he sees music as abstract shapes. The shapes he sees in different kinds of music are incorporated in the secular icons.

Pictured: Beckett explains some

fine points of color to

Theresa Rohter.

Icons are about the process of the creation as much as the result, said iconographer Lyons. “I think it’s very soothing. It’s a way to step out of our life in a very spiritual way ... it beats yoga!”

And besides, Lyons says, “We all love Ed. Without him, we wouldn’t be sitting here.”