by Laura Berthold Monteros

He’s been around the world, spending weeks and even months in exotic locations such as Africa, Asia, and the Himalayas, but when it came to choosing a place to live, Walt Disney Imagineer Joe Rohde chose Altadena.

Senior Vice President in the Creative Division of the Disney corporation, Rohde said “I like to live to the east of where I work.” That’s so the sun is always at his back, but he does appreciate having nature nearby. And well he might, as someone who goes to the farthest reaches of nature to bring it back in spirit to the Animal Kingdom theme park in Walt Disney World.

Senior Vice President in the Creative Division of the Disney corporation, Rohde said “I like to live to the east of where I work.” That’s so the sun is always at his back, but he does appreciate having nature nearby. And well he might, as someone who goes to the farthest reaches of nature to bring it back in spirit to the Animal Kingdom theme park in Walt Disney World.

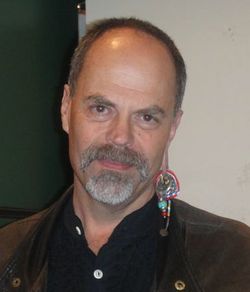

Pictured: Rohde buys earrings in every country he visits, and though he doesn't wear them all at one time, he did display a rather impressive collection on Friday night at the Pacific Asia Museum.

At Pacific Asia Museum’s Active Cultures lecture series on Friday, Rohde spoke about his quest to bring accuracy and “plausibility” to the latest ride, Expedition Everest. The challenge was to create a thrill ride that would mesh with the organization’s “deeply held principle of the intrinsic value of nature” and educate riders about conservation and culture.

And, of course about the yeti.

Rohde addressed the misconception that the Himalayas are nothing but snow-covered mountains. There are a great variety of climates in Tibet and Nepal, he said, and it changes from one to the other very quickly. Broadleaf evergreen forests, grasslands, valleys, rivers, plains—“It’s like all these islands came together and folded up,” he said. When settlers came, they found their niches according to the lifestyles of their ancestors.

Value of nature

The commitment of the Disney organization to nature is evident in the type of research Rohde and his crew did in the Himalayas. In addition to searching for material for the ride, the trip was a scientific expedition to look for undiscovered species—and they found several—and learn about indigenous cultures. Disney tried to do work where there were no legal protections for the land, and to supply the scientific dossiers to support preservation.

“Conservation International sent in their crack troops,” Rohde said. “In a very short time, they can do a very thorough analysis and make recommendations.

“Values drove us on this adventure, to make this discovery,” he said, peppering his speech with the mantra, “the intrinsic value of nature.”

In designing the ride and natural history section, the team was immersed in the art, architecture, culture, and crafts of the area. Some of the structures were built by Himalayan craftsmen, and they were consulted in modifying some of the images to be more plausible to Westerners. This was especially true with the image of the yeti.

Legend of the yeti

“The legend of the yeti was not so much the part we were interested in,” Rohde stated. “We were interested in the oral tradition of the yeti, in the cultural aspect of the creature.” With most of the Himalayas being heavily forested, Rohde said it is possible such a creature exists, and noted that when areas are deforested, the oral tradition of the yeti shifts to more classic folk stories like “how the sheep got its ears.”

He told a story about a Sherpa who showed them a yak, purportedly killed by a yeti. The skull was popped open and the brain eaten, a sure sign of a yeti kill. Rohde later asked a primatologist about this, and was told that it made sense. Primates are principally vegetarian, the expert said, but on occasion they would kill in just that way, and only the brain would be accessible to eat.

In the oral traditions, the yeti is a dual creature, simultaneously the spiritual protector of a natural enclave—portrayed as striped and cat-like—and the physical sasquatch-like primate typically thought of as the abominable snowman. As the protector of sacred areas, “the yeti is the spirit of the place,” Rohde said, “but it’s also a yeti who eats your yak.”

Wild places

The ability of the Tibetans and Nepalese to accept that the same creature can be two different things would be difficult to portray in a ride in a theme park in Florida, so the Imagineers had to come up with a plausible conflation of the two. Rohde explained, “When the yeti is in protector form, it doesn’t look like a ‘yeti.’ There had to be a translation between the source material and the final product that would be acceptable to Westerners.

“We don’t pretend what we did is a substitute for the real world, but it carries out the mission telling people, informing people, of the intrinsic value of nature.”

Rohde started working for Disney in 1980 and made a discovery of his own in 1982. He found Altadena before it was “discovered” and settled in. He may have traveled a lot, but for the past 30 years, he’s been an Altadenan. While he’s lived in several different homes, only once did he move a tad south to the metropolis below Woodbury. He likes the proximity to nature, the distinctive neighborhoods, the micro-climates, and the “wild, wild nature” of the place. He even impressed a safari-guide friend by taking him on a hike to Eaton Canyon.

“The guy was utterly thrilled,” Rohde enthuses. He was awed by the wildlife—deer, bears, snakes—that fill our woodlands and canyons. “We live next to one of the greatest areas,” Rohde said.

------

Laura Berthold Monteros writes about Altadena.