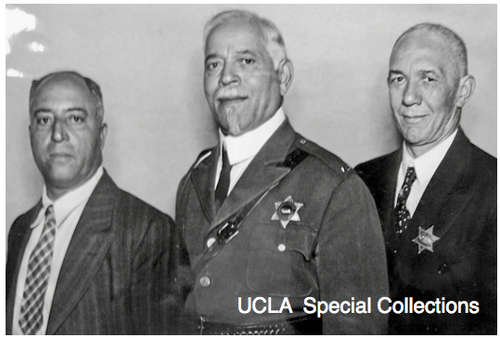

In this 1930's photo from his private collection, LA Sheriff's Deputy Julius Loving is flanked by two African American sheriff's deputies. One man’s identity is unknown; the other was R. C. Robinson.

by Sgt. John Stanley

Altadena Sheriff's Station

The Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department system of jailing has been at the cutting edge of reforms in penology for over a century. One of the unsung heroes, and the man responsible for the creation of many of its jail programs, was also the LASD’s first African American Deputy Sheriff: Julius Boyd Loving.

Julius Loving was born in 1863 in Washington, D.C. A Buffalo Soldier in the mid-1880’s, Loving moved to Los Angeles from Hartford, Connecticut in 1891 and quickly established himself as a businessman and leader in the city’s African-American community. Loving either founded or was a co-founder of many of the area’s African-American fraternal organizations.

He was a member and held leadership roles in the Elks, Foresters, United Brothers of Friendship and Knights of Pythias. He personally founded the Golden Leaf Court, which was the women’s chapter of the Knights of Pythias. His first wife Nannie was a leader in the Golden Leaf Court and the women’s auxiliary of the United Brothers of Friendship. In 1898, Loving was also elected the vice president of the city’s Afro American League, a forerunner of the NAACP. A few years later he would be the co-founder of a cooperative of African-American businessmen who established a building and loan to assist their fellows.

When William “Billy” Hammel was running for Sheriff in 1898, he promised the Afro American League that, if elected, he would appoint an African-American man as one of his deputies. Upon Hammel’s election many men vied for the position. Due to the often fractious infighting for the spot, Hammel offered it to Loving who was not even one of the men who was seeking the job. Hammel had done business with Loving’s hauling company and respected him. Loving accepted Hammel’s offer and was sworn in as a Los Angeles County deputy sheriff in January 1899.

Loving spent four years as a deputy sheriff and worked mostly in the jails, but he lost his position when Hammel was turned out of office in 1903 and most of his deputies were replaced by new men appointed by his successor Will White. This was a common practice in the days before civil service reform and Loving returned to his career in business working primarily in real estate.

The Class of '07

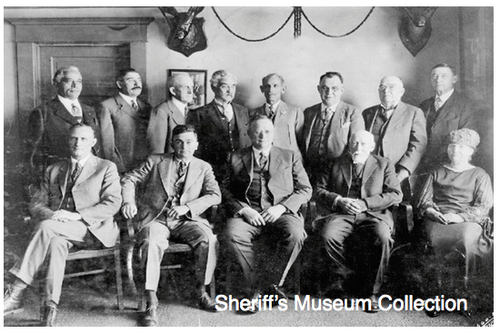

The Class of '07Hammel was re-elected Sheriff in 1906 and reinstated Loving as a deputy in January 1907. Hammel’s 1907 class of deputies was one of the most famous in department history. Among its distinguished members were former Sheriff Martin Aguirre, future Sheriffs William Traeger and Eugene Biscailuz and numerous other men who would end up in significant leadership roles on the department. In later years, these venerable Department pillars would be referred to as the “Old Guard” and Loving could be seen in every photograph commemorating an important anniversary of the group.

"Old Guard” Gathering at Hail’s Tavern on January 7, 1926. Standing from left to right: Julius Loving, Dan Crowley, Charles Bonnell, former Sheriff Martin Aguirre, E. Bert Rico, William T. Osterholt, Thomas Lancaster, George Shehi . Seated: Harry Wright, Undersheriff Eugene Biscailuz, Sheriff William Traeger, Juan Murrietta, Harriet Shehi.

Los Angeles County Sheriff's Museum collection.

Julius Loving’s work as a jail innovator began in earnest upon the beginning of Hammel’s second term in office. It would be accurate to consider Loving to be the father of jail programs. In 1908, he is credited as being one of the driving forces behind the creation of the first jail store. Due to Los Angeles County’s mushrooming population, its second jail, opened in 1886, was inadequate for the growing jail population and was replaced with a new structure in 1903. This facility received great praise in its early years, but creative ways of providing inmates with needed services economically was always a concern. The jail store helped with this as it sold tobacco, candy, and basic toiletries to inmates at cost. A variation of the jail store has been in existence ever since.

Loving is also acknowledged for introducing many of the jail’s inmate craft programs around this time. These included the jail carpenter shop, shoe shop, and tailor shop. All three were run by inmates and helped lower jail costs. He also invented a tote board that was used to maintain an accurate inmate count, a version of which is still in place in some jail modules today.

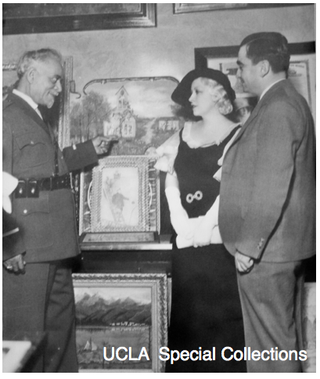

In 1913, Loving founded and supervised the Prisoners’ Art Exhibit which displayed paintings and other creative works produced by inmates. By the 1930s, the existence of the exhibit was so well known that Loving received letters from around the world praising him for his efforts to provide inmates with a meaningful rehabilitation program. Celebrities also visited the exhibit to offer their support. On one such visit in 1936, Mae West was photographed with Loving and Sheriff Eugene Biscailuz. (See photo).

In 1913, Loving founded and supervised the Prisoners’ Art Exhibit which displayed paintings and other creative works produced by inmates. By the 1930s, the existence of the exhibit was so well known that Loving received letters from around the world praising him for his efforts to provide inmates with a meaningful rehabilitation program. Celebrities also visited the exhibit to offer their support. On one such visit in 1936, Mae West was photographed with Loving and Sheriff Eugene Biscailuz. (See photo).

Advances in penology

Due to Loving’s accomplishments, Sheriff John Cline elevated Loving to the rank of inspector in 1918 and gave him oversight of all jail programs and maintenance. Thus, in addition to being the Los Angeles County Sheriff Department’s first African American deputy sheriff, he was also its first middle manager, as the rank of inspector was comparable to that of a lieutenant today.

As head of jail programs in the early 1920s, Julius Loving’s vigilance and creativity were often put to the test and his observation of inmate behavior was often valued in significant ways. In January and March 1920, Loving was credited with thwarting two escape attempts, and in February of that year he employed the threat of a fire hose to put down an inmate disturbance. In November 1922, Loving was one of many deputies who testified in the notorious trial of murderer Clara Phillips. Phillips bludgeoned a rival to death and her sanity was questioned. Loving was brought in to testify on that issue.

The ever expanding jail population reached its boiling point on March 9, 1921. On that date the largest jail riot in county history to that time erupted. Inmates erected barricades, started fires, and began tearing apart their cells. An even larger riot occurred twenty days later and lasted eighteen hours.

The March 9th riot occurred the very day that newly appointed Sheriff William Traeger took office. On a day that was supposed to be largely ceremonial, Traeger himself responded to the jail and helped put it down by use of a fire hose. After the larger riot at the end of the month, Traeger realized that a new direction was needed in the housing of prisoners. Traeger immediately began a work camp program. This was not another version of the chain gang so common in penology throughout the country. At Traeger’s work camps inmates helped to construct needed county roads and were paid to do so. There was very little supervision at these camps and the honor system was relied upon to keep inmates from fleeing far more than the handful of deputy sheriffs assigned to the facilities to oversee them. The success of the honor camps won Traeger nationwide acclaim, but it did not fully address the problems of overcrowding at the main jail.

Improving the jail system

Shortly after Traeger took office, the groundwork began for the construction of a new jail facility that in 1926 would result in the opening of Hall of Justice, which included the Hall of Justice Jail, and is still part of the Los Angeles skyline today. But in the years before HOJJ was ready for occupancy the problem of overcrowding in the old jail needed to be addressed. The work camps helped to reduce the population of lower security inmates, but the ever increasing numbers of higher security prisoners needed relief. Again it was Julius Loving who provided an answer. Loving designed a three-level bunk bed that helped alleviate jail overcrowding and eliminated the need for inmates to sleep on the floor. This solution helped to reduce growing jail tensions during the early 1920s.

Loving continued his role as head of jail programs until January 1937 when he retired after thirty-four years of service to the Sheriff’s Department. Loving was much admired on the Sheriff’s Department. At his retirement party he received many signed photographs from his long-time friends in the department wishing him well. These photographs are a prominent part of his scrapbook. Loving and Sheriff Biscailuz considered each other friends. Upon Loving’s death, his scrapbook was bequeathed to Biscailuz. This scrapbook can be viewed at the Eugene Biscailuz Collection at UCLA. (Some of the photos are included here.)

Loving continued his role as head of jail programs until January 1937 when he retired after thirty-four years of service to the Sheriff’s Department. Loving was much admired on the Sheriff’s Department. At his retirement party he received many signed photographs from his long-time friends in the department wishing him well. These photographs are a prominent part of his scrapbook. Loving and Sheriff Biscailuz considered each other friends. Upon Loving’s death, his scrapbook was bequeathed to Biscailuz. This scrapbook can be viewed at the Eugene Biscailuz Collection at UCLA. (Some of the photos are included here.)

Julius Loving, Dan Crowley, and T.W. Osterholtz standing behind Sheriff Eugene Biscailuz.

Julius Boyd Loving was a leader both within the Sheriff’s Department and Los Angeles County. Six months after he retired from the department, he helped found yet another organization when he was elected to the newly formed Los Angeles Eastside Chamber of Commerce. As he did in so many organizations, Loving served as the group’s treasurer.

An innovator and trailblazer

In a photograph in Julius Loving’s collection taken in the 1930s, he is flanked by two African American deputy sheriffs (see photo at top of article). One man’s identity is unknown; the other was R. C. Robinson, who would continue in service as a deputy sheriff for many years. Loving is wearing his full dress uniform. The other men are not in uniform, although R.C. Robinson’s badge is affixed to his coat. Loving appears quite proud of himself in this picture, and he had every right to be. One gets a sense of his awareness of his trailblazing role as the department’s first African American deputy sheriff from studying the photograph.

Loving died of heart disease on March 12, 1938. At his funeral, Sheriff Biscailuz ensured that the entire Sheriff’s Department was present to pay final tribute to him. There is no historical evidence that any other departed deputy or even sheriff was ever afforded this honor. There could be no more fitting tribute or declaration of the high regard with which Julius Loving was held by the Sheriff’s Department than for every man and woman on the force to be present at his funeral to pay their final respects. Loving’s prominent, heart-shaped headstone bears the insignia of the Elks, of his jail inspector’s badge, and displays the phrase, “A man among men who will always live in the hearts of those who knew him.”

Julius Boyd Loving was an innovator and trailblazer both for every African American deputy sheriff who followed him and all who ever worked in the Los Angeles County Jail system. His accomplishments deserve to be honored and remembered.

***

To learn more about the history of the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department, visit the Los Angeles County Sheriff's Museum, 11515 S. Colima Rd., Whittier, CA, 90604-2832.(562) 946-7859. Exhibits chronicle the history of the LASD. See an LASD helicopter and police vehicles from the past, explore an old west jail cell, see history on video and on display. Guided tours are available. Free admission (donations accepted).

-----

With a master's degree in history from Cal State Fullerton, Sgt. John J. Stanley is a published historian wrapped in a Los Angeles County Sheriff's Deputy uniform. This article is excerpted from Stanley's “Julius Boyd Loving: The First African American Deputy on the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department,” in the Southern California Quarterly, Winter 2011 – 2012, Volume 93, Number 4.