Being a test subject can be a small boy's biggest adventure

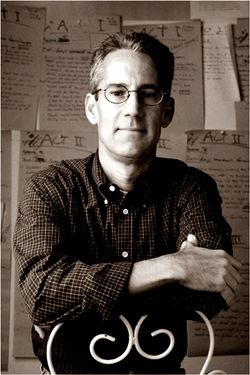

by Timothy Rutt

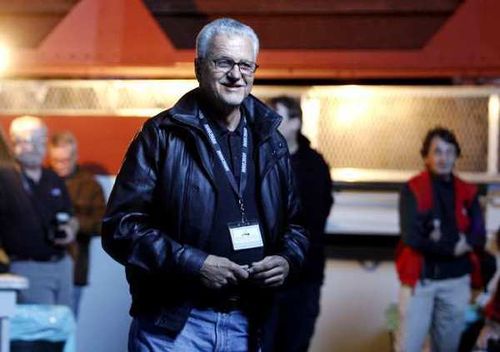

Jake Rutt shows off yet another injection as he tests a new muscular dystrophy medicine.

We don’t like to make too big a deal about our family. Every family, even the most normal-appearing, has crosses to carry and burdens to bear.

But some folks say we’re bearing more than most, and that may be true. For instance, there's our younger daughter Rosie, who has Down Syndrome. To her advantage, she’s high-functioning, as well as cute and affectionate, and is the star of the family show (we’ve written about her here and here).

Our son, Jake, 10, is a little more complex. He’s handsome, certainly, and charming when he wants to be, but he strikes darker notes than Rosie. He’s not uniformly sunny; he’s the one who gets lost in the shadows under Rosie’s bright star. He’s more brooding, feels things more deeply -- he’s a maelstrom of emotions that he sometimes can’t control.

Jacob, like Rosie, also was not a winner in the genetic lottery. Jacob couldn’t walk until he was two and a half, and our trips to the various medical specialists eventually yielded a diagnosis of Duchenne muscular dystrophy.

Life with Duchenne

Duchenne affects about one in every 3,500 boys (and it is almost entirely boys who have it). It’s nasty business -- when young, the naked Duchenne boy looks almost Herculean with his large, well-formed muscles, but that’s an illusion -- that’s fatty tissue and scar tissue, because his body is at war with itself -- those muscles don’t do much. The general prognosis in the past has been wheelchair at age 10, vent at age 20, and after that, well ...

The culprit is down in the genes -- missing exons, small bits of genetic matter, that throw the DNA helix off and interfere with the creation of dystrophin, which is necessary for muscles to develop normally.

There’s been a lot of progress lately, fortunately: boys with Duchenne are more mobile and longer-lived than ever. Jacob has been taking steroids for many years, which slows the progress of the condition although he pays for it by being a head smaller than his peers. He also has to take a drug usually given to old ladies with brittle bones to counteract the effects the steroids have on his skeleton. But there’s a lot of research going on, in this country and in Europe, that we hope will result in drugs to give him something closer to a normal life.

Once a year, he is evaluated at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital, which is one of the two best Duchenne clinics in the country. Through that, he was identified as a potential test subject for new drugs under development.